The transport layer entity interacts with both a user in the application layer and the network layer, to make the network layer’s data usable by applications. From the application’s viewpoint, the main limitations of the network layer service come from its unreliable service:

To deal with these issues, the transport layer includes several mechanisms that depend on the service than it provides between applications and the underlying network layer.

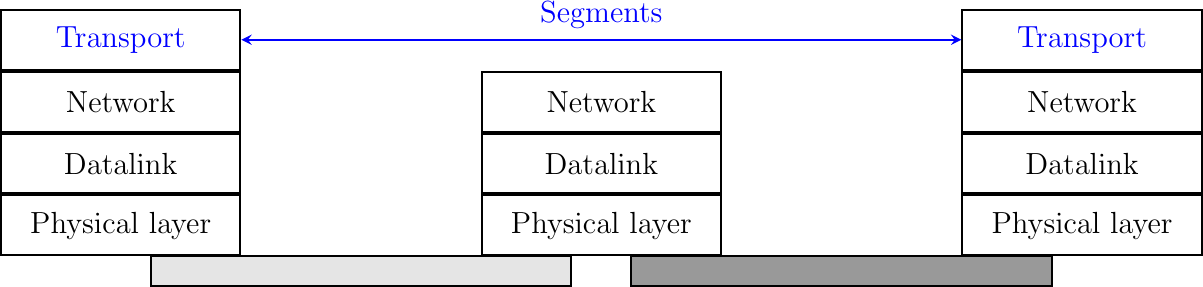

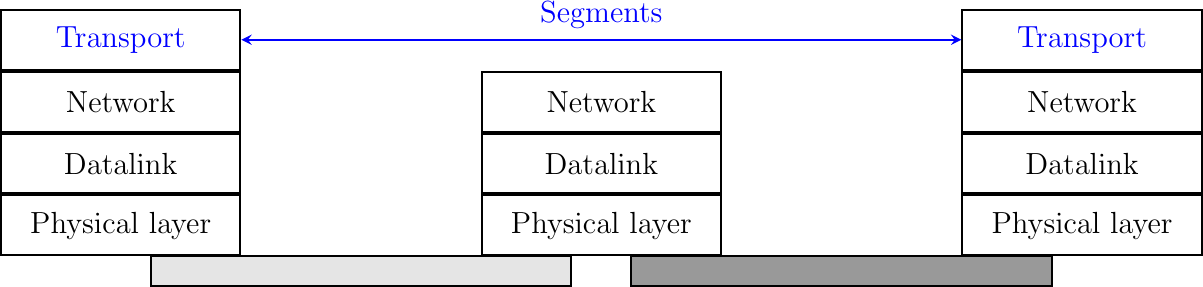

We have already described mechanisms to deal with data losses and transmission errors in our data link layer discussion. These techniques are also used in the transport layer. A network is always designed and built to enable applications running on hosts to exchange information. The principles of the network layer enable hosts connected to different types of data link layers to exchange information through routers. These routers act as relays in the network layer and ensure the delivery of packets between any pair of hosts attached to the network.

The network layer ensures the delivery of packets on a hop-by-hop basis through intermediate nodes. As such, it provides a service to the upper transport layer. Structuring this exchange of information requires solving two different problems. The first problem is how to represent the information being exchanged, given that the two applications may be running on hosts that use different operating systems, different processors, and different conventions to store information. This requires a common syntax between the two applications. Let us assume that this syntax exists and that the two applications simply need to exchange bytes. The second problem is how to organize the interactions between the application and the underlying network. From the application’s viewpoint, the network will appear as the transport layer service. This transport layer can provide connectionless or connection-oriented service.

The user datagram protocol (UDP) is a connectionless protocol designed for instances where TCP may have too much latency. UDP achieves this performance boost by not incorporating the handshaking protocol or flow control that TCP provides. The result is a speedy protocol that sometimes drops datagrams. UDP is often used as the basis for gaming or streaming protocols where the timing of the packets is more important than whether or not they all arrive. UDP does still employ checksums so you can be sure of the integrity of any UDP packets that you do receive.

The transmission control protocol (TCP) is at the heart of most networks, and provides for reliable communication via a three-way handshake. TCP breaks large data segments into packets, ensures data integrity, and provides flow control for those packets. This all comes at a cost, of course, explaining why this connection-oriented protocol typically has higher latency than its counterparts. Given the complex nature of TCP, it has often been targeted for attacks. TCP stacks are constantly adapting and changing (within the parameters of the protocol) to avoid DoS, DDoS, and MitM attacks.

What are some key differences between TCP and UDP?

Type of Connection

Reliability:

Speed:

Header Size:

Flow Control and Congestion Control:

Use Cases:

Common Ports and Services

A port number is used in a transport layer connection to specify which service to connect to. This allows a single host to have multiple services running on it. You may find many listeners on these ports as any user can have a service on them.

Applications use sockets to establish host-to-host communications. An application binds a socket to its endpoint of data transmission, which is a combination of an IP address and a port. A port is a software that is identified by a port number, which is a 16-bit integer value between 0 and 65535.

The Internet Assigned Numbers Authority (IANA)[/pb_glossary] has divided port numbers into three ranges. Port numbers 0 through 1023 are used for common services and called well-known ports. In most operating systems, administrative privileges are required to bind to a well-known port and listen for connections. IANA-registered ports range from 1024 to 49151 and do not require administrative privileges to run a service. Ports 49152 through 65535 are dynamic ports that are not officially designated for any specific service and may be used for any purpose. These may also be used as ephemeral ports, which enables software running on the host to dynamically create communications endpoints as needed.

Some commonly used ports and the services running on these ports may be subject to an attack. When scanning a machine, only necessary ports should be open. See below for some well-known ports.

File Transfer Protocol (FTP) Data Transfer

FTP Command Control

Secure Shell (SSH)

Telnet Remote Login Service

Simple Mail Transfer Protocol (SMTP) E-Mail

Domain Name System (DNS)

Dynamic Host Configuration Protocol (DHCP)

Trivial File Transfer Protocol (TFTP)

Hypertext Transfer Protocol (HTTP)

Post Office Protocol (POP3) E-Mail

Network News Transfer Protocol (NNTP)

Network Time Protocol (NTP)

Internet Message Access Protocol (IMAP) E-Mail

Simple Network Management Protocol (SNMP)

Internet Relay Chat (IRC)

Lightweight Directory Access Protocol (LDAP)

HTTP Secure (HTTPS) HTTP over TLS/SSL

Microsoft Terminal Server (RDP)

This video by Professor Dave Crabb provides an overview of how ports work with IP addresses to map to the correct application.

Next, we’ll look more closely at these two connection methods.

A reliable connectionless service is a service where the service provider guarantees that all SDU requests submitted in by a user will eventually be delivered to their destination. Such a service would be very useful for users, but guaranteeing perfect delivery is difficult in practice. Therefore, most networks support an unreliable connectionless service.

An unreliable connectionless service may suffer from various types of problems compared to a reliable connectionless service. First of all, an unreliable connectionless service does not guarantee the delivery of all SDUs. In practice, an unreliable connectionless service will usually deliver a large fraction of the SDUs. However, the delivery of SDUs is not guaranteed, so the user must be able to recover from the loss of any SDU. Second, some SDU packets may be duplicated in a network and be delivered twice to their destination. Finally, some unreliable connectionless service providers may deliver to a destination a different SDU than the one that was supplied in the request.

As the transport layer is built on top of the network layer, it is important to know the key features and limitations of the network layer service. The main characteristics of a connectionless network layer service are as follows:

So we see that the network layer is able to deliver packets to their intended destination, but it cannot guarantee their delivery. The main cause of packet losses and errors are the buffers used on the network nodes. If the buffers of one of these nodes becomes full, all arriving packets must be discarded. To alleviate this problem, the transport service includes two additional features:

To exchange data, the transport protocol encapsulates the SDU produced by its user inside a segment. The segment is the unit of transfer of information in the transport layer. When a transport layer entity creates a segment, this segment is encapsulated by the network layer into a packet, which contains the segment as its payload and a network header. The packet is then encapsulated in a frame to be transmitted in the data link layer.

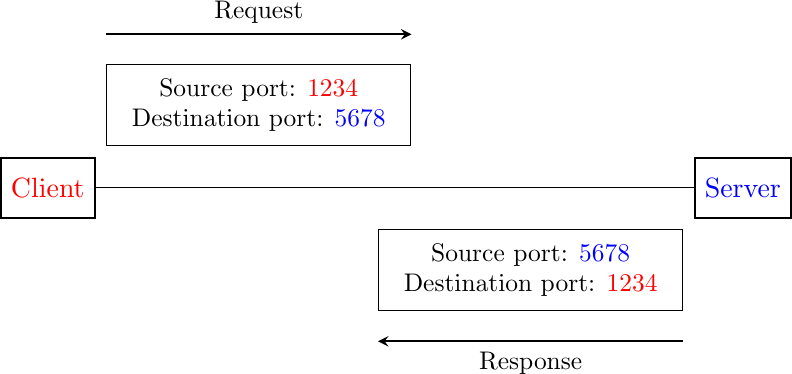

Compared to the connectionless network layer service, the transport layer service allows several applications running on a host to exchange SDUs with several other applications running on remote hosts. Let us consider two hosts, e.g., a client and a server. The network layer service allows the client to send information to the server, but if an application running on the client wants to contact a particular application running on the server, then an additional addressing mechanism is required, that is, a port. When a server application is launched on a host, it registers a port number. Clients use this port number to contact the server process.

The figure below shows a typical usage of port numbers. The client process uses port number 1234 while the server process uses port number 5678. When the client sends a request, it is identified as originating from port number 1234 on the client host and destined to port number 5678 on the server host. When the server process replies to this request, the server’s transport layer returns the reply as originating from port 5678 on the server host and destined to port 1234 on the client host.

To support the connection-oriented service, the transport layer needs to include several mechanisms to enrich the connectionless network-layer service. The connectionless service is frequently used by users who need to exchange small SDUs. It can be easily built on top of the connectionless network layer service that we have described earlier. Users needing to either send or receive several different and potentially large SDUs, or who need structured exchanges often prefer the connection-oriented service.

UDP is a widely used communication protocol for connectionless transport communication. Within an IP network, UDP does not require prior communication or a “handshake” to set up a channel or data path, and works with a minimum of protocol mechanisms. UDP does provide checksums for data integrity and port numbers for addressing different functions at the source and destination of the datagram; however, there is no guarantee of delivery, ordering, or duplicate protection.

UDP is suitable for purposes where error checking and correction are either not necessary or are performed in the application; UDP avoids the overhead of such processing. Time-sensitive applications often use UDP because dropping packets is preferable to waiting for packets delayed due to retransmission, particularly in real-time systems. The protocol was designed by David P. Reed in 1980 and formally defined in RFC 768.

A UDP datagram consists of a datagram header followed by a data section (the payload data for the application). The UDP datagram header consists of 4 fields, each of which is 2 bytes (16 bits).

The method used to compute the checksum is defined in RFC 768, and efficient calculation is discussed in RFC 1071. The checksum is the 16-bit one’s complement of the one’s complement sum of a pseudo header of information from the IP header, the UDP header, and the data. It is padded with zero octets at the end (if necessary) to make a multiple of two octets. In other words, all 16-bit words are summed using one’s complement arithmetic.

To perform this calculation, add the 16-bit values up. On each addition, if a carry-out (17th bit) is produced, swing that 17th carry bit around and add it to the least significant bit of the running total. Finally, the sum is then one’s complemented to yield the value of the UDP checksum field. If the checksum calculation results in the value zero (all 16 bits 0), it should be sent as the one’s complement (all 1s) as a zero-value checksum indicates no checksum has been calculated. In this case, any specific processing is not required at the receiver, because all 0s and all 1s are equal to zero in one’s complement arithmetic.

The differences between IPv4 and IPv6 are in the pseudo header used to compute the checksum, and that the checksum is not optional in IPv6. Under specific conditions, a UDP application using IPv6 is allowed to use a UDP zero-checksum mode with a tunnel protocol.

Lacking reliability, UDP applications may encounter some packet loss, reordering, errors, or duplication. If using UDP, the end-user applications must provide any necessary handshaking such as real-time confirmation that the message has been received. Applications such as TFTP may add rudimentary reliability mechanisms into the application layer as needed. If an application requires a high degree of reliability, a protocol such as TCP should be considered. Stateless UDP applications are beneficial in a number of applications, however. Streaming media, real-time multiplayer games, and voice over IP (VoIP) are examples of applications that often use UDP.

Real-time multimedia streaming protocols are designed to handle occasional lost packets, so only slight degradation in quality occurs, rather than large delays if lost packets were retransmitted. In these particular applications, loss of packets is not usually a fatal problem. In VoIP, for example, latency and jitter are the primary concerns. The use of TCP would cause jitter if any packets were lost as TCP does not provide subsequent data to the application while it is requesting a retransmission of the missing data.

Simple query-response protocols such as DNS, DHCP, and SMTP are suitable for UDP. UDP may also be used to model other protocols such as IP tunneling or RPCs. Because UDP supports multicast, it may be useful for service discovery (broadcast) information, such as Precision Time Protocol and Routing Information Protocol. Some VPNs such as OpenVPN may use UDP and perform error checking at the application level while implementing reliable connections.Finally, QUIC is a transport protocol built on top of UDP. QUIC provides a reliable and secure connection using HTTP/3, which uses a combination of TCP and TLS to ensure reliability and security respectively. This means that HTTP/3 uses a single handshake to set up a connection, rather than having two separate handshakes for TCP and TLS, meaning the overall time to establish a connection is reduced.

Watch this video by Ed Harmoush for an overview of which applications are best suited for UDP.

A connection-oriented protocol is a communication protocol that establishes a reliable, dedicated connection between two devices before transmitting data. The connection ensures that data is delivered in the correct order and without any errors. The connection is maintained throughout the communication and is terminated once the communication is over. If error-correction facilities are needed at the network interface level, an application may use Transmission Control Protocol (TCP) or Stream Control Transmission Protocol (SCTP) which are designed for this purpose.

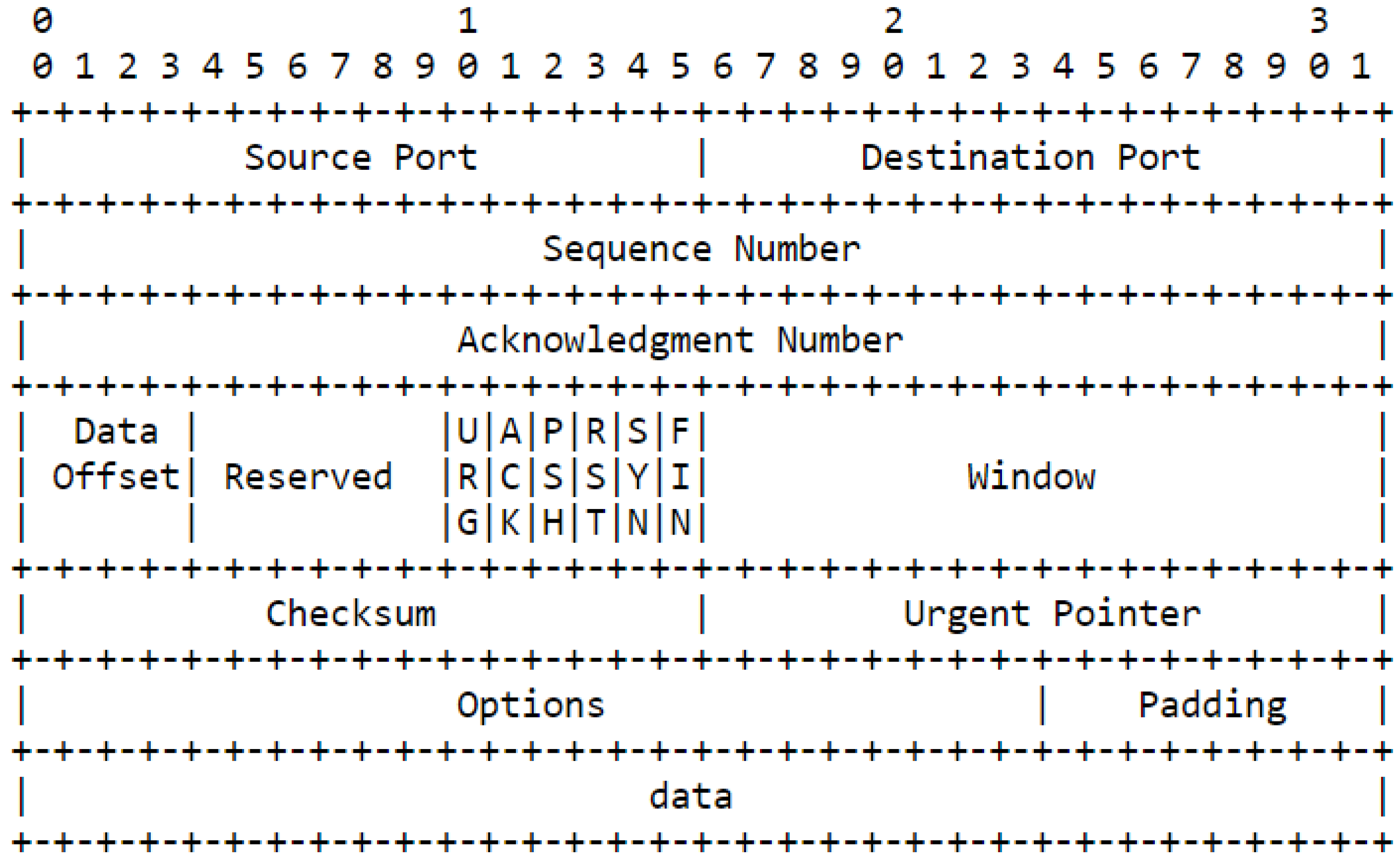

The TCP datagram header is the part of the TCP segment that contains information about the source and destination ports, sequence and acknowledgment numbers, flags, window size, checksum, and options. The TCP header has a minimum size of 20 bytes and a maximum size of 60 bytes. The TCP header format is shown below:

An invocation of the connection-oriented service is divided into three phases.

An important point to note about the connection-oriented service is its reliability. A connection-oriented service can only guarantee the correct delivery of all SDUs provided that the connection has been released gracefully. This implies that while the connection is active, there is no guarantee for the actual delivery of the SDUs exchanged as the connection may need to be abruptly released at any time.

Like the connectionless service, the connection-oriented service allows several applications running on a given host to exchange data with other hosts through designated port numbers. Similarly, connection-oriented protocols use checksums/CRCs to detect transmission errors and discard segments containing an invalid checksum/CRC. An important difference between the connectionless service and the connection-oriented one is that the transport entities in the latter maintain some state during the lifetime of the connection. This state is created when a connection is established and is removed when it is released.

The three-way handshake is a fundamental process in the Transmission Control Protocol (TCP). This process is used to establish a reliable and orderly communication channel between two devices (usually computers) before they begin exchanging data.

The three-way handshake in TCP consists of these steps:

At this point, the TCP connection is established, and both the client and server are synchronized, and can now reliably exchange data packets, knowing that the connection has been successfully established and that each party acknowledges the other’s readiness to communicate. This also helps in preventing unauthorized or forged connections, as both sides must agree on the initial sequence numbers and acknowledge each other before data transfer begins.

Now that the transport connection has been established, it can be used to transfer data. To ensure a reliable delivery of the data, the transport protocol will include sliding windows, retransmission timers and go-back-n or selective repeat. However, we cannot simply reuse the techniques from the data link because a transport protocol needs to deal with more types of errors than a reliable protocol in data link layer. First, the transport layer faces more variable delays in a network that can span the globe. This variability can be caused by two factors: packets do not necessarily follow the same path to reach their destination, and some packets may be queued in the buffers of routers, both leading to increased end-to-end delays. Second, a network does not always deliver packets in sequence. Packets may be reordered by the network and sometimes may be duplicated. Finally, the transport layer needs to include mechanisms to fragment and reassemble large SDUs.

TCP segments are typically sent in packets or frames over the network. Each segment is assigned a sequence number to ensure that data is received and reconstructed in the correct order at the destination. While reliable protocols in the data link layer use one sequence number per frame, reliable transport protocols consider all the data transmitted as a stream of bytes. In these protocols, the sequence number placed in the segment header corresponds to the position of the first byte of the payload in the byte stream. This sequence number allows detecting losses but also enables the receiver to reorder the out-of-sequence segments. Upon reception of the segments, the receiver will use the sequence numbers to correctly reorder the data.

TCP includes mechanisms for flow control to prevent the sender from overwhelming the receiver with data. The receiver can advertise a receive window size in its acknowledgments (ACKs), indicating how much more data it can accept before it needs the sender to pause and wait. Each transport layer entity manages a pool of buffers that needs to be shared between all its application processes. Furthermore, a transport layer entity must support several (possibly hundreds or thousands) of transport connections at the same time. This implies that the memory that can be used to support the sending or the receiving buffer of a transport connection may change during the lifetime of the connection. Thus, a transport protocol must allow the sender and the receiver to adjust their window sizes. To deal with this issue, transport protocols allow the receiver to advertise the current size of its receiving window in all the acknowledgments that it sends. The receiving window advertised by the receiver bounds the size of the sending buffer used by the sender. TCP uses the sequence numbers in segments to reassemble data in the correct order before passing it up to the higher-layer application. What if segments arrive in the wrong order? If two consecutive segments are reordered, the receiver relies on their sequence numbers to reorder them in its buffer. Unfortunately, as transport protocols reuse the same sequence number for different segments, if a segment is delayed for a prolonged period of time, it might still be accepted by the receiver. T o deal with this problem, transport protocols combine two solutions. First, they use 32 bits or more to encode the sequence number in the segment header. This increases the overhead, but also increases the delay between the transmission of two different segments having the same sequence number. Second, transport protocols require the network layer to enforce a Maximum Segment Lifetime (MSL) . The network layer must ensure that no packet remains in the network for more than MSL seconds. On the Internet, the MSL is assumed to be 2 minutes ( RFC 793 ). Note that this limits the maximum bandwidth of a transport protocol. If the sender doesn’t receive an ACK within a certain timeout period or if it receives duplicate ACKs indicating missing data, it retransmits the unacknowledged segments. This retransmission continues until all data is successfully delivered or a predefined maximum number of retries is reached.

The four-phase connection termination process in the Transmission Control Protocol (TCP) is used to gracefully close a TCP connection after data transfer is complete. This process ensures that all remaining data is delivered, and both the sender and receiver agree to terminate the connection. The four phases of the TCP connection termination process can be summarized as follows:

Figure 6-7: The TCP four-phase connection termination

The FIN-WAIT-1, FIN-WAIT-2, CLOSE-WAIT, and LAST-ACK states are transient states that the sender and receiver go through during the termination process. After these four phases, the TCP connection is considered closed. Both the sender and receiver have acknowledged their intent to close the connection, and any remaining data has been sent and acknowledged.

TCP uses a reliable and orderly process for connection termination to ensure that no data is lost or left unacknowledged during the closure. This graceful termination process is designed to maintain the integrity and reliability of data transmission over the connection until the very end. Once the LAST-ACK state is reached, both sides consider the connection closed, and the resources allocated for that connection can be released.

Watch this video by Ben Eater to see a walkthrough of a TCP connection.

The sections above were adapted from the following sources:

Transmission Control Protocol (Wikipedia, last updated 21 Sept 2023), licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

“TRAP: A Three-Way Handshake Server for TCP Connection Establishment” Applied Sciences 6, no. 11: 358. https://doi.org/10.3390/app6110358. Fu-Hau, Yan-Ling Hwang, Cheng-Yu Tsai, Wei-Tai Cai, Chia-Hao Lee, and KaiWei Chang, 2016. ; MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article, license under CC-BY.